A Midyear Review of NC’s Labor Market

During the first half of 2010, North Carolina’s job market essentially ran in place. Although jobs were not lost at the frantic pace of 2008-09, little progress was made. Conditions remained weak, and growth did not occur at the level needed to re-absorb displaced workers or accommodate new entrants to the labor force. And considerable evidence suggests that more difficulties are in store for the the second half of 2010.

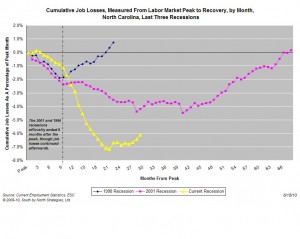

The figure (right) shows the job losses that occurred in North Carolina between December 2007 and May 2010, the most recent month with data. Over that period, North Carolina lost, on net, 254,000 positions or 6.1 percent of its payroll job base. Between September 2008 and April 2009, the state lost an average of 23,450 jobs per month. Losses slowed during the summer of 2009 before bottoming in September. Since then, the state has gained an average of 5,000 jobs per month.

The figure (right) shows the job losses that occurred in North Carolina between December 2007 and May 2010, the most recent month with data. Over that period, North Carolina lost, on net, 254,000 positions or 6.1 percent of its payroll job base. Between September 2008 and April 2009, the state lost an average of 23,450 jobs per month. Losses slowed during the summer of 2009 before bottoming in September. Since then, the state has gained an average of 5,000 jobs per month.

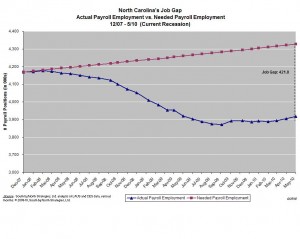

Unfortunately, North Carolina needs to add some 5,500 positions per month to keep  pace with workforce growth. If one considers the jobs that should have been created during the recession but were not, the actual gap facing the state is 422,000 positions (Figure, left).

pace with workforce growth. If one considers the jobs that should have been created during the recession but were not, the actual gap facing the state is 422,000 positions (Figure, left).

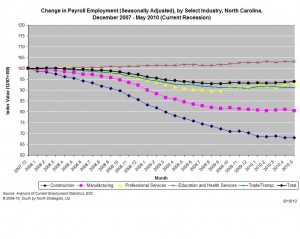

While the job growth posted in 2010 is welcome, it is insufficient. The state has netted 31,300 jobs, but only 14,100 of those jobs are private-sector ones. As the figure ( below) shows, selected private industries have posted little growth.

below) shows, selected private industries have posted little growth.

Meanwhile, many of the public-sector jobs that the state gained were temporary ones, primarily positions related to the 2010 Census. These jobs now are ending. In fact, the Census Bureau’s Charlotte region (NC, KY, TN, and VA) eliminated 27,748 jobs between the weeks of May 12th and June 12th.

At current rates of monthly job growth, which are much lower than those recorded after the bottom of the 2001 recession, it would take North Carolina until late 2014/ early 2015 just to replace the lost payroll positions, to say nothing of the jobs that should have been created but were not.

Faster rates of growth would reduce that time span (a growth rate similar to the one following the 2001 recession would bring about a payroll recovery by mid-2013), yet little evidence suggests that faster growth is imminent. Much of the growth that has occurred in 2010 is attributable to public policy supports like recovery act spending, extended unemployment insurance benefits, homebuyer tax credits, and temporary census hiring. Many of those programs are ending, and it is unclear what will take their place in supporting overall demand.

Take two examples. First, the expiration of the federal Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC) program will pull money out of the state’s economy. In May, EUC benefits supported an estimated $383 million in statewide economic activity; the phase-out of the program gradually will reduce that amount to zero. Second, cuts in state spending tied to reductions in federal aid will further remove demand from the economy. The U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, for example, estimates that reductions in state and local spending subtracted 0.5 percentage points from the nation’s gross domestic product during the first quarter of 2010.

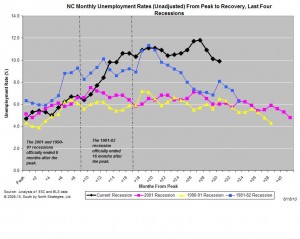

In light of such developments, North Carolina’s unemployment rate is apt to remain at a high level. During this recession, the unemployment rate surpassed the highest one recorded since the advent of modern records in the 1970s (and likely would be even higher if adjusted for changes in the workforce’s age structure). Unemployment also has surpassed the highest levels recorded during any recent recession (Figure, right).

In light of such developments, North Carolina’s unemployment rate is apt to remain at a high level. During this recession, the unemployment rate surpassed the highest one recorded since the advent of modern records in the 1970s (and likely would be even higher if adjusted for changes in the workforce’s age structure). Unemployment also has surpassed the highest levels recorded during any recent recession (Figure, right).

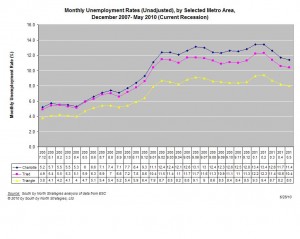

Unemployment has increased across the state, and in May, 53 counties posted double-digit unemployment rates (unadjusted) with 21 counties recording rates of at least 12 percent. Last month, 10.8 percent of the non-metropolitan labor force was unemployed, as was 9.5 percent of the metropolitan labor force. And unemployment remains elevated in the state’s three largest metro areas — Charlotte, the Research Triangle, and the Piedmont Triad (Figure, left); growth in these areas is vital to any long-term recovery.

counties posted double-digit unemployment rates (unadjusted) with 21 counties recording rates of at least 12 percent. Last month, 10.8 percent of the non-metropolitan labor force was unemployed, as was 9.5 percent of the metropolitan labor force. And unemployment remains elevated in the state’s three largest metro areas — Charlotte, the Research Triangle, and the Piedmont Triad (Figure, left); growth in these areas is vital to any long-term recovery.

In May, 10.3 percent of the workforce (seasonally-adjusted rate) was unemployed, and in actuality, an even greater share of the population was effectively jobless yet excluded from the official count. Young workers and minority workers in particular have struggled during the recession. And while job losses have abated, those who are unemployed face a dearth of openings. As a result, the problem of long-term unemployment is growing.

If the pattern of long-term unemployment is not reversed by late 2010 or early 2011, many individuals will become effectively unemployable due to the deterioration of their skills, stiff competition, and negative stereotyping. At that point, a serious cyclical employment problem will become a more intractable structural one.

The second half of 2010 likely will be a challenging time for working North Carolinians, especially those who have been jobless for long periods. Both personal and business spending are apt to remain subdued as households pull back on spending due to uncertainty about the labor market and a desire to rebuild lost wealth. Weak consumer demand, in turn, will hold back business spending. Additionally, the expiration of the federal policy supports mentioned previously and state budget cuts will remove more spending from the economy.

Absent more aggressive federal action, the second half of 2010 likely will prove no better — and perhaps will prove more trying — than the first half of the year.

Email Sign-Up

Email Sign-Up RSS Feed

RSS Feed