10.11.2011

Policy Points

Economic policy reports, blog postings, and media stories of interest:

10.11.2011

Policy Points

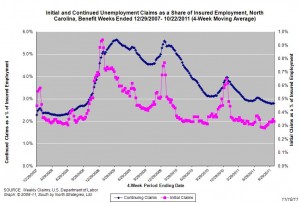

For the benefit week ending on October 22, 2011, some 11,547 North Carolinians filed initial claims for state unemployment insurance benefits, and 105,200 individuals applied for state-funded continuing benefits. Compared to the prior week, there were fewer initial and continuing claims. These figures come from data released by the U.S. Department of Labor.

Averaging new and continuing claims over a four-week period — a process that helps adjust for seasonal fluctuations and better illustrates trends — shows that an average of 12,446 initial claims were filed over the previous four weeks, along with an average of 104,566 continuing claims. Compared to the previous four-week period, the average number of initial claims was lower and the number of continuing claims was higher.

One year ago, the four-week average for initial claims stood at 14,514 and the four-week average of continuing claims equaled 116,752.

While the number of claims has dropped over the past year so has covered employment. Last week, covered employment totaled 3.72 million, down from 3.73 million a year ago.

The graph shows the changes in unemployment insurance claims (as a share of covered employment) in North Carolina since the recession’s start in December 2007.

The graph shows the changes in unemployment insurance claims (as a share of covered employment) in North Carolina since the recession’s start in December 2007.

Both new and continuing claims appear to have peaked for this cycle, and the four-week averages of new and continuing claims have fallen considerably. Yet continuing claims remain at an elevated level, which suggests that unemployed individuals are finding it difficult to find new positions.

10.11.2011

Policy Points

From the Economic Policy Institute’s analysis of the September version of the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) …

By comparison, in December 2000 the job-seeker’s ratio was 1.1-to-1. Furthermore, the highest this ratio ever got in the early 2000s’ downturn was 2.8-to-1. September marks just over three years in a row that the job-seeker’s ratio has been at or above 3-to-1. Put another way: We’ve been above the highest level of job seekers to jobs reached in the early 2000s’ recession for the last three years. And we’ve been substantially above 4-to-1 for the last two years and nine months. A job-seeker’s ratio of more than 4-to-1 means that for more than three out of four unemployed workers, there simply are no jobs. Because the job-seekers ratio has been above 4-to-1 for this long—two years and nine months or 143 weeks—the extended unemployment insurance benefits, which last a maximum of 99 weeks, remain crucial.

09.11.2011

Policy Points

Economic policy reports, blog postings, and media stories of interest:

09.11.2011

Policy Points

Crooked Timber considers the impact that the European Union’s “democracy deficit” is having on its response to the economic crisis.

… European politicians have preferred to integrate by stealth rather than public debate. But they cannot do that any more. They have tried repeatedly, and failed repeatedly, to treat the rolling crisis as another, albeit much more complicated, technocratic problem, which can be solved through the usual kind of technocratic solution. As they started to do this, European Union governance shifted from the so-called “Community method” (under which decisions were taken by rough consensus among the member states, with the Commission acting as a kind of neutral buffer), to Angela Merkel’s Union method in which the member states were supposed to take decisions on their own. This in turn hasn’t worked out very well (Germany and France disagree on quite a lot), leading to the effective governance of the European Union by the European Central Bank (what might be called, for all its perplexities, the “ECB method”). Each of these steps has led to an ever greater remove between actual decision making and democratic control. But, when you are asking people to accept a fundamentally different way of ordering politics than the one that they are used to, lack of democratic input is a problem. What is being debated at the moment is not a technocratic fix to Europe’s problems of economic stability. It is a long term set of institutional arrangements which, if they succeed, will shape Europe’s politics for generations to come, and if they fail will likely take the world economy down with them.

Email Sign-Up

Email Sign-Up RSS Feed

RSS Feed