12.01.2011

Policy Points

The Economix blog published by The New York Times recently asked why Americans’ in the top 10 percent of the income distribution don’t consider themselves to be well-0ff. The answer: the people above them in the income distribution are just “so much richer.”

The line [graph] gets much steeper because at the very top of the income scale, the monetary divisions between percentiles grow much greater. Those in the middle earn a little less than people a few percentiles up from them, whereas those at the top earn a lot less than their counterparts in nearby, higher percentiles. For example, those who aspire to hop from the 30th percentile to the 35th percentile would need in increase their cash income by $4,000 annually (or by about 17 percent); those who aspire to hop from the 91st percentile to the 96th percentile would require an increase of $324,900 (or 171 percent).

…

In other words, at least in dollar terms, there is much greater inequality at the very top of the income scale than at the bottom or in the middle. Whether this translates to much greater differences in standards of living at the top is debatable, as an extra $1,000 for a poor family likely makes a much bigger impact on that family’s quality of life than an extra $1,000 for a wealthy family.

12.01.2011

Policy Points

In a thoughtful column in The New Yorker, James Surowiecki asks why public resentment at unions is growing.

The result is that it’s easier to dismiss unions as just another interest group, enjoying perks that most workers cannot get. Even though unions remain the loudest political voice for workers’ interests, resentment has replaced solidarity, which helps explain why the bailout of General Motors was almost as unpopular as the bailouts of Wall Street banks. And, at a time when labor is already struggling to organize new workers, this is grim news. In a landmark 1984 study, the economists Richard Freeman and James Medoff showed that there was a strong connection between the public image of unions and how workers voted in union elections: the less popular unions were generally, the harder it was for them to organize. Labor, in other words, may be caught in a vicious cycle, becoming progressively less influential and more unpopular. The Great Depression invigorated the modern American labor movement. The Great Recession has crippled it.

11.01.2011

Policy Points

Economic policy reports, blog postings, and media stories of interest:

11.01.2011

Policy Points

The Baseline Scenario weighs in on the interactive tax expenditure database recently compiled by the Pew Charitable Trusts.

Tax expenditures primarily benefit the rich, for a few reasons.

—

First, most of them are deductions from taxable income, which means their value to you is proportional to your marginal tax rate….

—

Second, because most of them are itemized deductions, you only get them if you itemize your deductions–which usually means either that you have a big enough house to have a big mortgage or you have enough income to pay a lot of state and local taxes.

—

Third, the size of the deduction is highly correlated with income. To take the most obvious example, rich people have bigger houses, and so they have bigger mortgages….

—

Fourth, there are the tax expenditures that you get on investments, which are disproportionately held by the rich. There’s the tax exemption for life insurance investments. There’s the big one: tax-advantaged investment accounts, including 401(k)s, IRAs, Roth IRAs, 529s, etc….

—

Fifth, there are the tax expenditures for businesses, since in theory those flow to their shareholders, who are disproportionately the rich….

11.01.2011

Policy Points

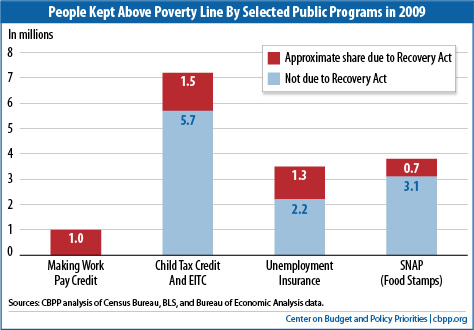

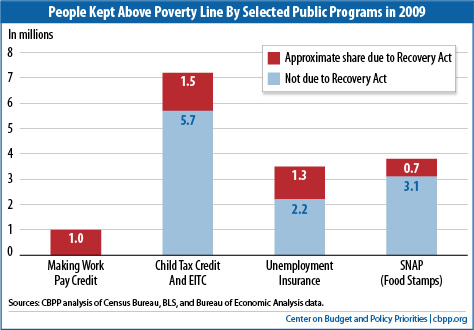

A Center on Budget & Policy Priorities analysis of poverty data for 2009 found that public policy supports contained in the recovery act kept 4.5 million Americans out of poverty.

Email Sign-Up

Email Sign-Up RSS Feed

RSS Feed